Mycology photographs courtesy of Gordon Walker

Without warning, our lives can be turned upside-down. We can arrive to a place where we truly belong though, if we look to nature for guidance —brush your hands through the Willow tree, breathe in the aroma of the Datura (Solanaceae), strike up a conversation with the slender gametophyte of the Hibiscus. From this enchantment, we are revived; simultaneously relieved from our ego- for as a culture we have forgotten the virtue and essence of nature’s impact.

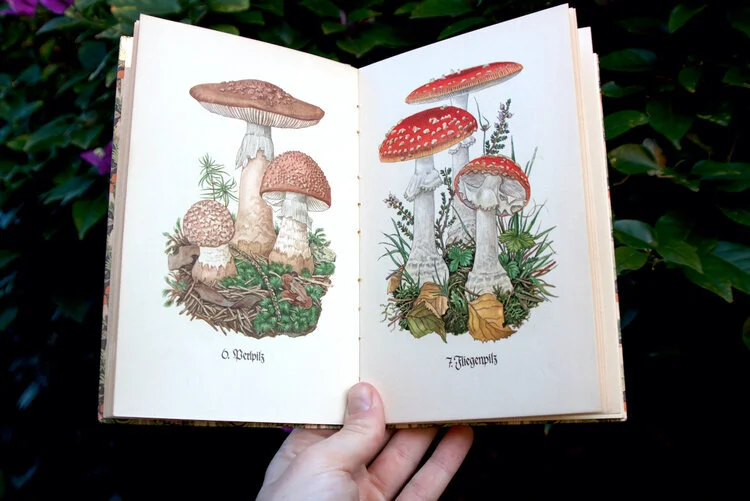

Ever so recently I had picked up a few books on Mycology, in hopes of deciphering the majestic kingdom of the mushroom. I had found myself head over heels, when discovering this one very specific German antiquarian book:

Das Kleine Pilzbuch — pictured: Perlpilz, Amanita rubescent (left) and Fliegenpilz, Amanita mascara (right). Einheimische Pilze each der Natur gezeichnet von Billi Harmerth, 1956. Infel-Bucherei Nr. 503.

Eventually I'd arrived to becoming profoundly moved by these findings, although I had soon felt the urge to speak with a present day naturalist. I called around at a few plant nurseries, and wrote a dozen emails. And to my surprise, one of those individuals had gotten back to me: Gordon Walker, a PHD Graduate from UCDavis, and resident of Napa Valley. He maintains a beautifully curated page, @fascinatedbyfungi, where he documents all of his fungi findings - such as happy slime molds from plasmodiums, and further elaborates on certain species, like the Craterellus.

Being intrigued by his individual discoveries, I had a few questions to ask him -in ordinance of digging a little deeper into Gordon's process and passion, as a Phenologist, and bringing more attention to the significance of his work. He is not only a teacher, but a mentor in ways that should not be overlooked.

Gina Jelinski: What are some of your favorite smells, from any one fungi?

Gordon Walker: I love the aroma of different mushrooms, there is an amazing variety of smells they produce. Two of my favorites are the almondy agarics (mushrooms that smell like marzipan), and the candy cap mushrooms that smell like maple syrup (Sotolon). I also love the smell of dried porcini powder, and many other dried mushrooms -as the drying process enhances umami, and deepens the aromas.

GJ: I was hoping you might share with us how your interest with fungi first took place?

GW: As a child I had several experiences that made me intensely interested in fungi, but the fascination didn’t fully blossom until a couple of years ago when I started my @fascinatedbyfungi account. As a child I would go up to the woods of Quebec to stay at my grandparents cabin, walking around in the woods I would see many types of mushrooms. I remember finding, and being particularly enchanted by, a slimy green parrot mushroom -the Gliophorus psittacinus, my grandfather had identified for me. I also remember finding and eating a giant puffball mushroom, as we all spent our time harvesting chicken of the woods, and honey mushrooms from trees in our yard.

GJ: How is it that mushrooms bear more similarities to animals and insects? I have read about there being a common misconception of fungi being related to plants.

GW: Evolutionarily fungi are closer the animal kingdom than plants are. Insects and fungi both contain chitin (a nitrogen containing polysaccharide) unlike plants, which are primarily composed of cellulose. Fungi share more metabolic similarities with animals in that they are both consumers of organic matter rather than photosynthetic creators.

Walker states the following in his observation of the Craterellus (pictured above): "...a species of the famed “Winter Trio”...these delicately fluted mushrooms with gorgeous highly textured ridges belong to the Yellow Foot Chanterelles, or the Craterellustubaeformis (sometimes known as the Winter Chanterelle). This is a ectomycorrhizal species that can also grow saprophytically on decaying logs and on fallen leaf litter (often found near redwood duff in California). Like other chanterelles they have white spores, “false gills” (ridges seen here) and “decurrent” gills that run down onto the stipe (stem) of the mushroom."

GJ: What are issues that you have recently monitored out in nature?

GW: In my local park I observe the ecology of the Oak Chapparal Woodland. Many of the oak trees are sick, infected with Sudden Oak Death (Phytopthera ramorum), a plant pathogen that weakens the immune system of the trees. SOD leads to the oak trees being infected by pathogenic fungi (honey mushrooms (Armillaria), Lions mane (Hericium), Jack O’ Lantern Mushrooms (Omphalotus). I also witnessed all of the Eucalyptus trees in Napa get infected with Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus gilbertsonii), it weakens the heartwood of the trees which causes them to fall into vineyards, crushing grape vines.

GJ: Might you inform us on the specific types of creatures that appear to be attracted to fungi?

GW: Slugs and snails are my favorite animals to find eating fungi, they are also some of the most voracious and can quickly plow through mushrooms you might otherwise want to eat. Mushrooms support a wife range of insect life, they are essential to biodiversity and are the foundation of all of our ecosystems (especially given the role they play in the nitrogen cycle).

GJ: I'd love if you could tell us more about the slugs and snails, Gordon.

GW: The Ariolimazcalifornicus species complex. This hungry sluggo is going to town on a bounty of Fat Jacks (Suilluscaerulescens). Arilomax are some of the largest slugs in the world and can live 1-7 years. The two sets of tentacles they use to sense the world, the two top ones have primitive eye spots that sense light and motion, the bottom two are chemical sensing. They mate as simultaneous hermaphroditic pairs, although one member of the pairing will occasionally eat the penis of the other, potentially as a source of nutrient or as a competition/dominance thing (do your own research into it, Banana slug videos are wild). This Suillus species is mycorrhizal with Doug-Fir and makes a pretty decent edible if picked young and prime.

GJ: You also have some bewildering self-portraits with a few different species, one I particularly admire is the one where you are holding the Cauliflower mushroom -it's a massive creature!

GW: This Western version of the Cauliflower Mushroom tends to grow on conifers (pines and fir). It is a brown rot or butt rot fungi that will occur on the same tree year after year. Colloquially, I have heard that Sparassis lasts for quite awhile after being picked. Like many fungi, Sparassis contain a multitude of antibacterial, antifungal, cytotoxic, and immunostimulatory compounds. All of these various activities help the fruiting bodies of Sparassis last quite awhile, dispersing many spores and giving the fungi the best chance of survival. "

GJ: Being a witness to the miraculous life of the animal kingdom, what might you say, aside from patience, is a requirement in the field of mycology? And, what would you recommend as a means to begin studies, for a blossoming mycologist?

GW: Mycology is vast, requiring many different personalities to tackle the range of topics. I think a keen eye, passion, persistence and scientific mindset are the great assets for a budding myco-enthusiast.

Get a regional specific field guide. I like “Mushrooms of the Redwood Coast” for California and the PNW. Make an account on iNaturalist and or Mushroom Observer (the latter being more intermediate to advanced). Take photos, start uploading observations and interacting with the community online.

“Join a local mycology club, and go on forays. Be a good listener and respect nature.”

Walker's recent foraging collection -mixed hardwood mushrooms of the Eastern Forests, Cape Ann, and Dogtown.

Gordon states: "The mixed hardwoods of the eastern forests support a rich variety of mycorrhizal fungi that fruit abundantly in the warm wet summer months of the north east. Cape Ann gets battered by famed Nor’Easters in the cold dark winters but in the long muggy summer days fungi come out to play (so do mosquitos and ticks)."

GJ: Gordon, are there any specific myths that you enjoy reading about?

GW: I prefer data and peer review, to myths. Although I am fond of Norse mythology, Scandinavian/Nordic cultures value mushroom foraging and have many stories involving fungi.

The Berzerker was a common Nordic warrior said to have "fought with a trance-like rage" and instead of wearing armor they "wore a coat made out of a bear's skin".

GW: Mythology has stated that the hallucinogenic mushroom Amanita muscaria is responsible for such an infamous history, although most historians have recently abandoned this theory.

GJ: In making the assumption that you have a green thumb, I was curious as to what species we might find in your garden?

GW: I am growing a winter garden with French breakfast radishes, mache, fennel, bok choy, and onions. I also have mushroom beds for 3 kinds of oyster mushrooms, shiitake, wine caps, and blewits.

GJ: Do you think that carnivorous plant life gets along with fungi -if they were the last two creatures alive on this planet...or would they work against one another in a sense?

GW: Carnivorous plants are adapted to anoxic nutrient poor bogs, there is very little fungal activity in that type of environment because it is dominated by anerobic bacteria. Carnivorous plants are dependent on insects for nitrogen, as opposed to the nitrogen deposited into soils via organic degradation by fungi.

Mushrooms can have a variety of relationships with plants. 90% of plant life has a mycorrhizal fungal partner, and many plants also contain endophytes: fungi that live in between plant cells, acting as an innate immune system for the plant. There are also parasitic fungi that prey on plants, leading to a wide variety of common fungal diseases for agriculture.

Lion's mane (Hericiumerinaceus) —Like most mushrooms, Lions Mane contains beta-glucans (fungal polysaccharides) which can stimulate our immune systems and support a healthy microbiome. There is potential for Lions Mane to produce other bioactive compounds with anti-microbial/inflammatory/cancer, properties as well. According to recent papers (Vi M, et al. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2018.) and (Ofosu FK, et al. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2016.) the production of these compounds can be modulated by substrate composition and treatment during growth.

The Yellow Leg Bonnet (Mycenaepipteryga) —a small saprobic fungi that grows on decaying conifers and in grasslands, it’s is a basisionycete with white spores. These mushrooms are also known to be bioluminescent (probably to attract insects at night to help disperse spores).